DELTA’S RAIN GARDEN PROGRAM FOR STREETSCAPE REVITALIZATION: “Road designers have a major influence on the future condition of a watershed,” states Hugh Fraser, former Deputy Director of Engineering, City of Delta

Note to Reader:

Published by the Partnership for Water Sustainability in British Columbia, Waterbucket eNews celebrates the leadership of individuals and organizations who are guided by the Living Water Smart vision. Storylines accommodate a range of reader attention spans. Read the headline and move on, or take the time to delve deeper – it is your choice! Downloadable versions are available at Living Water Smart in British Columbia: The Series.

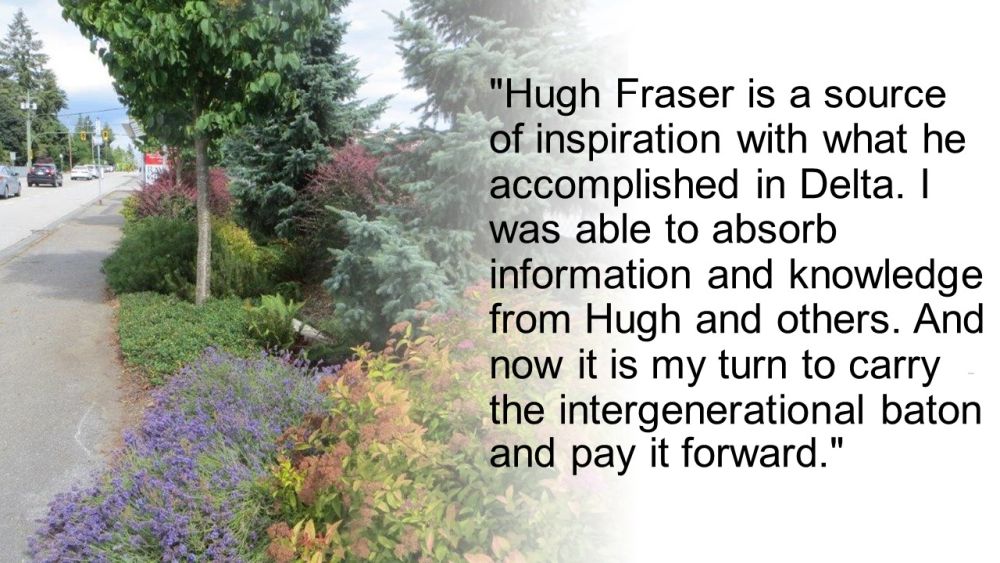

The edition published on April 9, 2024 featured the City of Delta’s rain garden program for streetscape revitalization. Now in Decade Three, the program is driven by a vision for protection of stream health through the use of green infrastructure that captures and sinks road runoff. The story behind the story is told by Hugh Fraser and Harvy Singh Takhar and showcases the passing of the intergenerational baton from Hugh to Harvy.

Delta’s rain garden program for streetscape revitalization

Hugh Fraser successfully guided the City of Delta through the first two decades of its green infrastructure journey and streetscape revitalization program. He is an original “streetscape enhancement champion” in the Metro Vancouver region.

When Hugh Fraser retired in 2021, he handed the intergenerational baton to Harvy Singh Takhar to provide green infrastructure inspiration going forward. Harvy is following his passion in unexpected ways because it was happenstance that led him down the green roof pathway to international recognition.

The Partnership previously featured Harvy S. Takhar in Living Water Smart in British Columbia: Looking at green roofs through a water balance lens, a story published in 2023.

Road designers have a major influence on watershed condition

“Historically, drainage has been an afterthought in urban planning decisions. Neighbourhoods were developed without thinking about drainage in a broader watershed context,” states Hugh Fraser.

“Circa 2000, however, the emphasis became let’s look at this on a watershed basis. For municipalities like Delta with well developed infrastructure, this meant figuring out HOW to retrofit and redesign drainage systems.”

“Road rights-of-way account for one-third of the land area of a typical urban watershed. From the rainwater management and stream health perspective, in Delta we believed that commitment to a rain garden program would make a material difference over time.”

“When Delta re-builds roads, streetscape enhancement is part of the capital budget. For the program to be effective, and the changes in practice to be lasting, everyone in the process must care about the big-picture goal.”

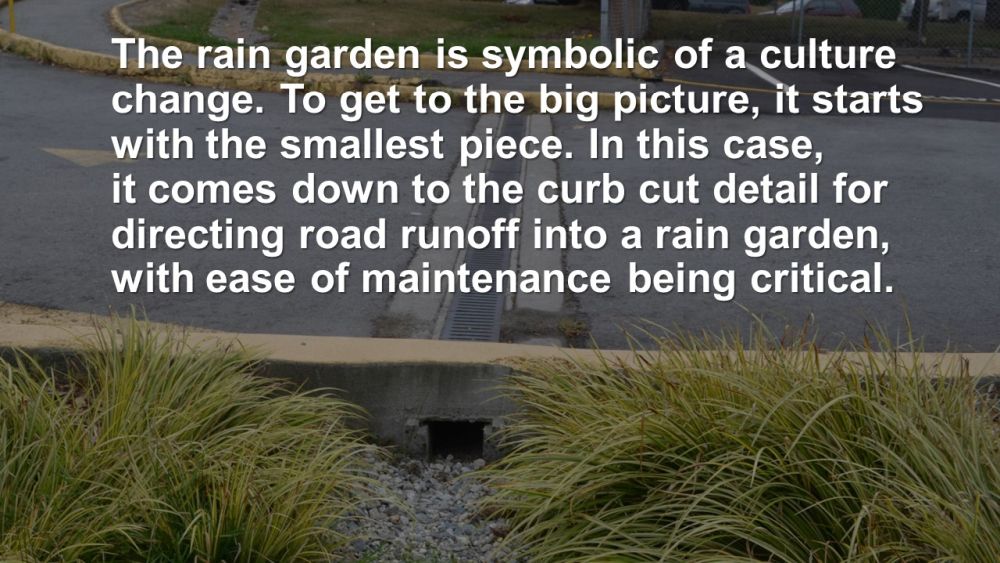

“In the early years, it required constant reminders to staff about the WHY. We asked designers to think about HOW to incorporate something as simple as curb cuts to direct road runoff into boulevard rain gardens. And we added a landscape designer (Sarah Howie) to the engineering design team.”

“I had the privilege of carrying on from Hugh Fraser and Sarah Howie,” continues Harvy S. Takhar. He is one of Delta’s two Utilities Engineers. “It does feel like the rain garden ethic is embedded in the culture of the organization. Curb cuts for drainage is normal practice.”

EDITOR’S PERSPECTIVE / CONTEXT FOR BUSY READER

“Hugh Fraser is a green infrastructure pioneer in the Metro Vancouver region. In the early 2000s, Hugh was a leading voice on Metro Vancouver’s Stormwater Interagency Liaison Group when green infrastructure was in its infancy,” stated Kim Stephens, Waterbucket eNews Editor and Partnership Executive Director.

“At the time, this regional group had energy. And they made things happen under the umbrella of the rainwater (aka “streams and trees”) component of the region’s first Liquid Waste Management Plan (LWMP).”

“The regulatory requirement for this plan component flowed from the Fish Protection Act 1997 which itself was a watershed moment as Susan Haid explained in the April 2nd edition of Waterbucket eNews.”

“Delta’s rain garden program began in the 2000s as a demonstration application for operationalizing the region’s LWMP to achieve desired watershed health outcomes. The program is now in Decade Three. Shared responsibility and intergenerational commitment are foundation pieces for enduring success.”

Delta’s rain garden program is a team effort

“The intergenerational aspect of passing the baton within local government intrigues me. One of the things Hugh Fraser told me many years ago was about the need, as he saw it, to embed the green infrastructure ethic in the culture of the municipal organization and community at large,” continued Kim Stephens.

In 2014, Hugh Fraser provided this perspective:

“Everyone involved…students, designers, managers, constructors and operators…must understand and care about the big-picture goal. This is a team effort,” stated Hugh Fraser.

“Yes, we are making progress on the public side, but there is much more that can be done on the private side. The opportunities to work with property owners to retrofit rain gardens result from redevelopment, especially in commercial areas.”

“Creating a watershed health legacy will ultimately depend on how well we are able to achieve rainwater management improvements on both public and private sides of a watershed. There is a huge up-side if the private sector embraces their contribution to shared responsibility.”

Rain gardens cumulatively contribute to restoration of stream health

“Delta urban areas are built out,” states Hugh Fraser. “This reality means there are limited opportunities for slowing, spreading and sinking rainwater. The municipality is effectively limited to retrofitting of rain gardens within road corridors in order to provide rainwater infiltration that protects stream health.”

“Delta has some 500 kilometres of roadways. In 2005, the municipality embarked upon a long-term initiative to incrementally improve the urban landscape though a streetscape revitalization program. The corporate vision is to enhance community liveability by beautifying streets, one block at a time.”

Story behind the story

With the foregoing in mind, Kim Stephens stated that: “Curiosity prompted me to have a 3-way conversation with Hugh Fraser and Harvy S. Takhar about Delta’s rain garden program. Three years after Hugh’s retirement, I wondered, what intergenerational perspective Harvy would bring to what Hugh started? That is the story behind the story!”

STORY BEHIND THE STORY: Delta’s rain garden program for streetscape revitalization – extracts from conversations with Hugh Fraser and Harvy Takhar

The “story behind the story” weaves quotable quotes into a storyline. Quotes are extracted from interviews included in a legacy resource that the Partnership will release later in 2024.

“Delta’s rain garden program started with a phone call from Deb Jones, a volunteer with the Cougar Creek Streamkeepers. She expressed her wish to do a ‘ditch-scaping’ project as she described it in front of her house,” recalls Hugh Fraser.

PART ONE: Rain garden at Cougar Canyon Elementary School launched the program

“Deb Jones was passionate and persistent. In 2004, Deb and her group approached me with a request that the municipality undertake a stormwater pilot infiltration pilot project in North Delta. We identified the opportunity to build the first rain garden at Cougar Canyon Elementary School.”

“The project was collaborative and involved the Cougar Canyon students. The project was a success and so too was the ensuing program. Within the first decade, for example, Delta had constructed a total of 50-plus rain gardens. 10 of these were located at elementary schools.”

“Delta rain garden projects are not cookie-cutter designs. Each site is unique; and there will always be constraints and challenges. Fortunately, rain gardens are adaptable, and the approach in Delta was adaptive from day one. That means learn by doing.”

Rain Garden at Cougar Canyon Elementary School

Adopt-a-Rain-Garden: To address the need for ongoing maintenance:

PART TWO: Influence of road designers on watershed condition and stream health

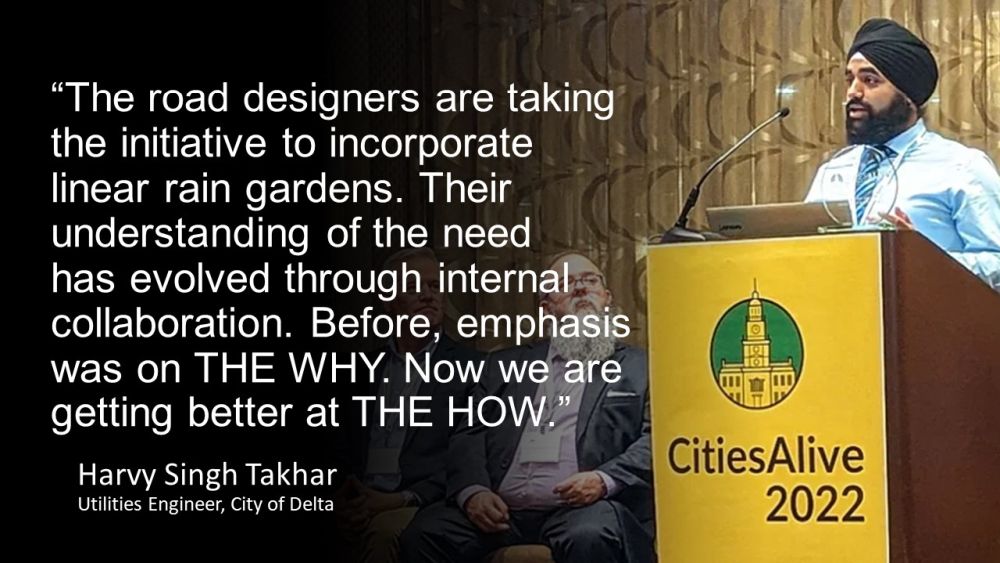

“We have done a lot of back and forth on road designs,” continues Harvy S. Takhar. “The streetscape enhancement ideology is being implemented at the forefront rather than through a review of utilities to see whether there any drainage concerns.”

“The road designers are taking the initiative to incorporate curb cuts and even linear rain gardens. Their understanding of the need has evolved through internal collaboration. Before, emphasis was on THE WHY. Now we are getting better at THE HOW.”

|

|

Pay the intergenerational baton forward

“And we have more staff buying in which is really important. Nina Tong, an engineer in training, represents the third generation of rain garden designers. She follows Sarah Howie and me. Nina has been instrumental in running some current green infrastructure projects.”

“She is now evolving into the design and ideological aspects and how we look for opportunities to incorporate rain gardens. It is about being hands-on and proactive. My message to Nina and others is, do not be afraid to hop in there and show our operations people the opportunities.”

|

|

Living Water Smart in British Columbia Series

To download a copy of the foregoing resource as a PDF document for your records and/or sharing, click on Living Water Smart in British Columbia: Delta’s rain garden program for streetscape revitalization.

DOWNLOAD A COPY: https://waterbucket.ca/wcp/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2024/03/PWSBC_Living-Water-Smart_Delta-rain-gardens-and-streetscape-revitalization_2024.pdf

About the Partnership for Water Sustainability in BC

Technical knowledge alone is not enough to resolve water challenges facing BC. Making things happen in the real world requires an appreciation and understanding of human behaviour, combined with a knowledge of how decisions are made. It takes a career to figure this out.

The Partnership has a primary goal, to build bridges of understanding and pass the baton from the past to the present and future. To achieve the goal, the Partnership is growing a network in the local government setting. This network embraces collaborative leadership and inter-generational collaboration.

TO LEARN MORE, VISIT: https://waterbucket.ca/about-us/

DOWNLOAD: https://waterbucket.ca/atp/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/2024/01/PWSBC_Annual-Report-2023_as-published.pdf