PATH FORWARD FOR GROUNDWATER IN BRITISH COLUMBIA: “The fact that BC has such small aquifers suggests that they likely get more local than provincial attention,” states Mike Wei, former Deputy Comptroller of Water Rights

Note to Reader:

Published by the Partnership for Water Sustainability in British Columbia, Waterbucket eNews celebrates the leadership of individuals and organizations who are guided by the Living Water Smart vision. Storylines accommodate a range of reader attention spans. Read the headline and move on, or take the time to delve deeper – it is your choice! Downloadable versions are available at Living Water Smart in British Columbia: The Series.

The edition published on March 26, 2024 featured Mike Wei, former Deputy Comptroller of Water Rights in British Columbia. An invitation to appear before a House of Commons Standing Committee gave Mike Wei a reason to step back, see things from afar, and describe what a path forward for groundwater management could look like in BC.

Path forward for groundwater in BC

The House of Commons’ Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development is currently doing a study on Canada’s freshwater. In February, the committee invited British Columbia’s Mike Wei to speak on federal policy, legislation and activities with a focus on groundwater.

The Canada Water Agency, created in 2023, provided context for interaction with the committee. Members asked Mike Wei for his thoughts and insights. His reflections form the basis for the story behind the story that follows. His observation is that we view water differently in BC and in profound ways.

So, why would the House of Commons committee seek out Mike Wei? Is it because he is knowledgeable and credible in three insightful ways?

One, he was the Province’s technical expert in developing and implementing groundwater legislation.

Two, Mike Wei was in the room and helped write the legislation for the Water Sustainability Act.

Three, he is a member of a small band of former civil servants who represent the Province’s institutional memory for water and remain committed to the “water-centric mission”.

Competing priorities and the wait for a provincial “water champion” to emerge

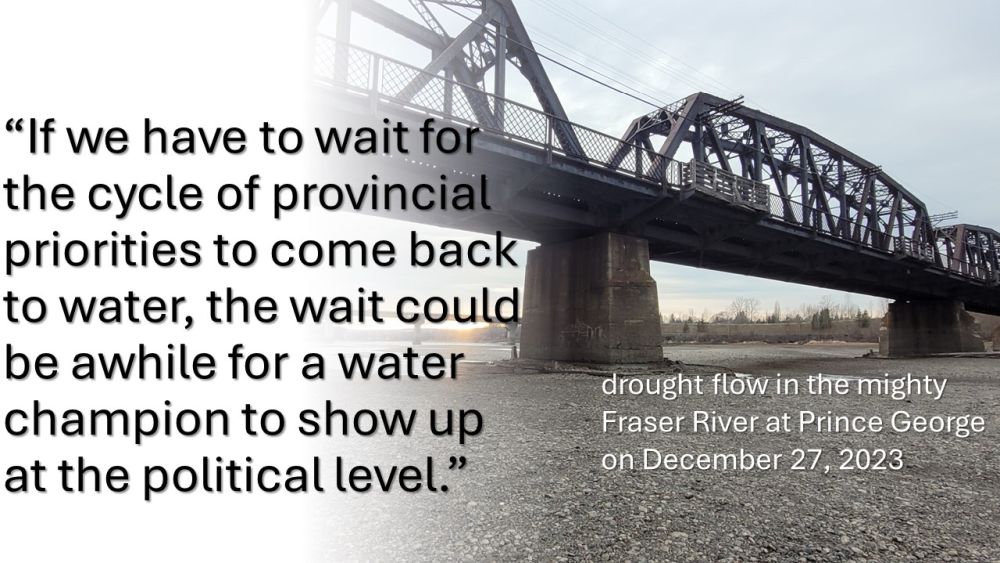

In his exchange with the committee, Mike Wei observed: “Given all that I have seen in BC over my 40-year career – recession in the 1980s, political instability in the 1990s, current crises in housing and food affordability, drug overdoses, health care system for an aging population, gang violence, etc., it will be difficult for water to receive sufficient and sustained attention from the BC government alone.”

“Canada’s investment and collaboration, done in a spirit of enabling provincial and territorial capacity to manage water would allow us to keep moving forward. Doing it by ourselves will only mean stalled efforts as other issues take priority time and again.”

EDITOR’S PERSPECTIVE / CONTEXT FOR BUSY READER

“Nominally the story is that Mike Wei went to Ottawa to talk about groundwater. But that is not the story behind the story. Mike Wei is passionate about water. He cares, he really cares about getting it right at a pivotal moment in British Columbia history,” stated Kim Stephens, Waterbucket eNews Editor and Partnership Executive Director.

“Weather extremes. Drying rivers, frequent wildfires. Our land ethic has consequences. The water balance is out of balance. We need both a mindset change and an attitude switch. Mike Wei, as an ambassador of the Partnership, is involved in an ongoing conversation about how to reconcile this need.”

“His meeting with the House of Commons committee created an opportunity for reflection by Mike Wei. It gave him a reason to step back, see things from afar, and describe what a path forward could look like. In the story behind the story, Mike Wei presents broad brush solutions in clear terms.”

Learn to look back to see ahead

“Getting it right means understanding the historical context for surface and groundwater management in this province. This requires that decision makers at all levels learn to look back to see ahead.”

“Mike Wei’s over-arching message is that BC needs help because water invariably gets bumped by other priorities.”

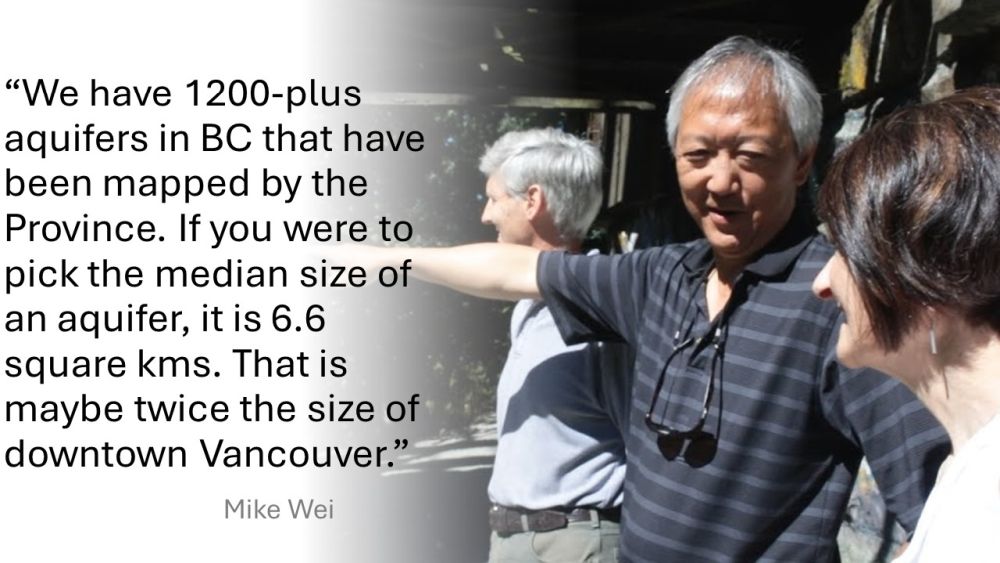

“It got my attention when Mike pointed out that the 1200 mapped aquifers are typically tiny. And so they are ignored because they are not viewed as important. But you live and die at that scale.”

“So, what is the path forward that Mike Wei suggests? Well, it has three elements that make sense to me.”

Unless it is legislated, it is not a priority

“In theory, few would argue against a science-forward approach to inform legislative design,” Mike Wei stated during our conversation.

“It is common knowledge that government-mandated commitments and legislation inform government budgets,” he continued. “Prior to the coming into force of the Water Sustainability Act in 2016, the BC government was less likely to prioritize and fund comprehensive groundwater studies.”

“The reason is that it had no legislated mandate to protect or manage that resource, especially as the BC government underwent budgetary constraints in response to the economic recession in the 1980s and political instability in the 1990s.”

“The lesson from BC is that the historical regulatory context cannot be ignored in regulatory design,” Mike Wei emphasized.

STORY BEHIND THE STORY: Think beyond water flows downhill – extracts from a conversation with Mike Wei

“The House of Commons’ Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development is currently doing a study, as they called it, on freshwater. They had two sessions on groundwater, each with a panel of four. I was the only one who spoke from a government perspective,” explained Mike Wei when he set the scene.

Water issues are not the same across Canada

|

|

“If we have to wait for the cycle of provincial priorities to come back to water, the wait could be awhile for a water champion to show up at the political level.”

“And so my message to the committee was that WE NEED HELP from the federal government. Helping us build infrastructure and capacity is an obvious way to help. Lending their scientific arm to do projects with us would be really helpful as well.”

BC’s Water Sustainability Act is a guide for scientific enquiries and collaboration

“But I also cautioned that, from my observer perspective, the various federal water programs seem disconnected. Not that they have to be totally coordinated but they do have to be consistent.”

“Virtually all of the federal groundwater people, for example, are in Ottawa and Quebec. It is very difficult for them to come here and build relationships and do studies.”

“While BC did have a very strong relationship with the Geological Survey of Canada as recently as ten years ago, we did not have the Water Sustainability Act (WSA) to guide our scientific enquiries. Now we do.”

First, deploy the WSA legislative framework to ask the right questions

“Before the WSA became law in 2016, we did not know exactly what scientific questions to ask. For example, we knew in our minds that hydraulic connection between surface and groundwater was important. But we did not know if the government thought that way because it was not written in law.”

“A big lesson for me is that the WSA legislation gives us that framework to ASK THE QUESTIONS THAT ARE IMPORTANT to that legislation.”

“The science forward approach which some academics advocate is a good idea but has practical challenges. When groundwater was vested in 1960, the Province did start the groundwater program with a science forward approach.”

“But we did not have the legislated context to ask the right questions. Legislation drives scientific questions; in turn, science informs legislation. It is not a one-time thing, but rather iterative.”

|

|

Next, protect the local interest and do it well; and do it well everywhere

“Going forward, any science that is done should involve the public. We need the mass of citizenry to understand that surface and groundwater are connected, and hydraulic connection and response are important concepts.”

“In rural regions, the agricultural sector is one of the biggest users of water in BC watersheds. The more agricultural water users understand that hydraulic connection and response are important, the more likely it is they will support and comply with the WSA.”

“Something that I have been thinking about a lot is that 1200-plus aquifers in BC have been mapped by the Province. If you were to pick the median size of an aquifer, it is 6.6 square kilometres. That is maybe twice the size of downtown Vancouver. This is tiny.”

Build partnerships that are top-down and bottom-up

“The importance of aquifers that are of limited extent needs to be viewed in a different way. Instead of comparing them to the immense size of BC, compare them within a more local context.”

“Because these aquifers of limited size are a priority for local communities and local governments, there is an opportunity for the Province to leverage this local interest and work with local governments and communities. It is about having an attitude that encourages forming local partnerships to deal with resources which are of limited size but equally as important as big ones.”

“It is very much a bottom-up, grassroots thing. We need to build more partnerships for water sustainability because local interest is significant and provides momentum that cannot come from the Province alone.”

Living Water Smart in British Columbia Series

To download a copy of the foregoing resource as a PDF document for your records and/or sharing, click on Living Water Smart in British Columbia: Think beyond water flows downhill.

DOWNLOAD A COPY: https://waterbucket.ca/wcp/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2024/03/PWSBC_Living-Water-Smart_Mike-Wei_think-beyond-water-flows-downhill_2024.pdf

About the Partnership for Water Sustainability in BC

Technical knowledge alone is not enough to resolve water challenges facing BC. Making things happen in the real world requires an appreciation and understanding of human behaviour, combined with a knowledge of how decisions are made. It takes a career to figure this out.

The Partnership has a primary goal, to build bridges of understanding and pass the baton from the past to the present and future. To achieve the goal, the Partnership is growing a network in the local government setting. This network embraces collaborative leadership and inter-generational collaboration.

TO LEARN MORE, VISIT: https://waterbucket.ca/about-us/

DOWNLOAD: https://waterbucket.ca/atp/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/2024/01/PWSBC_Annual-Report-2023_as-published.pdf