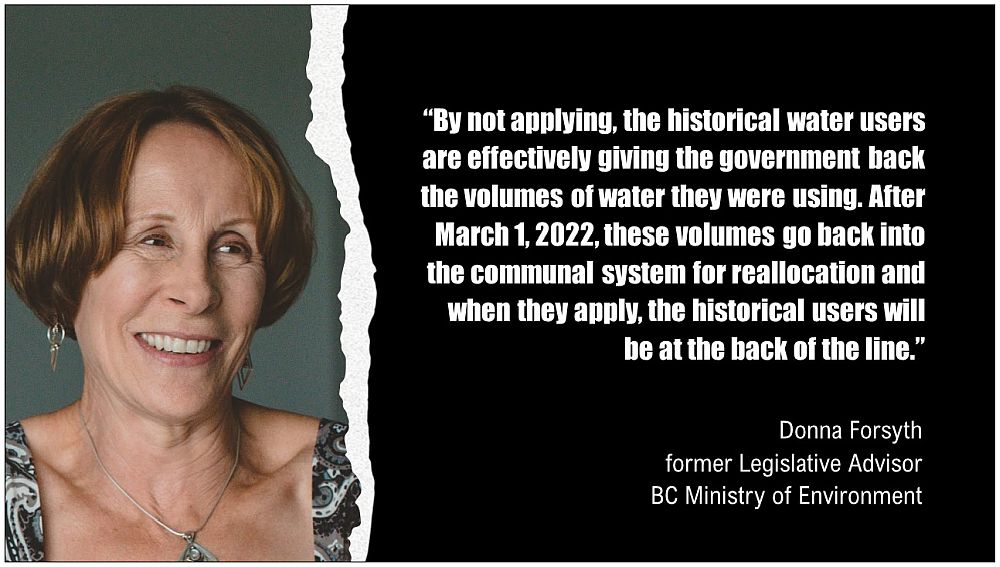

THE EMERGING CRISIS AROUND GROUNDWATER LEGISLATION IMPLEMENTATION IN BRITISH COLUMBIA: “By not applying, the historical water users are effectively giving the government back the volumes of water they were using. After March 1, 2022, these volumes go back into the communal system for reallocation and when they apply, the historical users will be at the back of the line,” stated Donna Forsyth, former Legislative Advisor in the Ministry of Environment (May 2021)

Note to Reader:

In 2016, water management in BC entered a new era with passage of the Water Sustainability Act. The WSA made it a legal requirement that all non-domestic groundwater users in BC be licensed or otherwise authorized. Until then, only water users drawing from surface sources had been regulated in BC. Now, groundwater users were required to play by the same set of rules. At the time, there were an estimated 20,000 non-domestic groundwater users in BC. They were given three years to apply for licences.

Trouble is Brewing Around Groundwater Licensing in BC

Groundwater licensing is a foundation piece of the Water Sustainability Act that was passed in 2016. March 1, 2022 is the deadline for historical non-domestic groundwater users to apply for a licence to retain their right to divert and use groundwater.

The problem, explains Donna Forsyth (former Legislative Advisor in the Ministry of Environment), is that, of the estimated 20,000 historical groundwater users, a mere 4,000 have reportedly submitted applications. Moreover, government decisions on these applications are taking 3 or more years, which is undermining the confidence of rural water users and potentially discouraging others from complying with the requirement to licence their wells.

“When the government changed the rules with the WSA, it recognized that it was placing a new regulatory burden on historic groundwater users and gave them time to continue using their water while they applied for the licences,” says Donna Forsyth.

“Now, the time to get those applications in is running out. If historic, non-domestic water users don’t get their licence applications in by March 1 2022, they’ll not only lose their authority to use the water, but they could experience a gap of years before a decision is made on their applications.”

“In addition, since these late licenses will not recognize previous water use, they will lose their seniority and therefore be the first to be cut off in times of water scarcity.”

To Learn More:

Read the news release from the Partnership for Water Sustainability: Trouble is Brewing Around Groundwater Licensing in British Columbia.

Groundwater Licensing – Why “Getting It Right” Matters!

Four Key Messages

“Obtaining a licence is not an upgrade to a groundwater user’s previous common law rights. The common law rights ceased to exist when the Water Sustainability Act came into force in 2016,” states Donna Forsyth.

“By not applying for a groundwater licence, the historical water users are effectively giving the government back the volumes they were previously using. After March 1, 2022, these volumes go back into the communal system for reallocation and when they apply, the historical users will be at the back of the line.”

“For applications submitted after the transition period ends, the user loses the authority to continue using the groundwater while the application is being adjudicated, even if that takes years. The transition period was set up to prevent disruption of operations for historical groundwater users, but that protection is over on March 1,2022.”

“After March 1st, applications may be significantly more expensive due to additional costs associated with new applications, including impacts on stream environmental flow needs.”

Implications of Groundwater Licensing for Food Security Issue

“I am especially passionate about this issue because a significant number of groundwater users are irrigating crops for food and operating food processing facilities,” continues Donna Forsyth. “I am not an expert in this, but I worry about crop failures when food producers lose their ability to irrigate.”

“This will happen unless they retain their right to keep using groundwater by applying for their groundwater licence before the deadline. My understanding is that the risks are especially high in the case of fruit trees, vines and shrubs that require years of cultivation.”

“These food producers have already been struggling to maintain operations during the pandemic due to COVID-related risks to their employees. The danger of these businesses not surviving goes up exponentially if they have no legal access to groundwater.”

Impacts to Land Value

“We are hearing that some landowners who are historical non-domestic groundwater users think that they will be okay because they don’t think the government will enforce the groundwater licensing requirement.”

“They need to consider that the value of most rural properties is generally aligned with the availability of water. Water licences are tied to the land and pass with the transfer of land, so the existence of a groundwater licence will be crucial to any purchaser wanting to use groundwater on the property for any non-domestic purpose.”

“Also, if the historical groundwater user misses the deadline, they run a much greater risk of their licence being rejected due to the hydraulic connection of their well to a fully allocated stream. At best, after the deadline they will receive the most junior priority date when their application is granted (even if the farm had been using that water for decades).”

“In many areas of the province, the change to this junior priority date will dramatically affect the value of the land. This is because, in B.C., when there is not enough water for all users, the most junior licences must stop using their water first.”

Groundwater Licensing Needs to be a Top Government Priority

“When the WSA was passed, all parties in the legislature agreed that managing groundwater was a very high priority. For the past six years, the implementation of groundwater licensing by FLNRO (Ministry of Forests, Land and Natural Resource Operations) has been consistently under-prioritized for a variety of reasons.”

“It’s not too late to get ‘all hands on deck’ to ensure the successful implementation of this crucial part of the WSA package. It starts with clearly communicating the implications of the changes to historical non-domestic groundwater users,” concludes Donna Forsyth.

To Learn More:

Download a copy of Living Water Smart in British Columbia: The Emerging Crisis Around Groundwater Regulation Implementation, a call to action released by the Partnership for Water Sustainability in April 2021 to draw attention to the serious nature of the issue. Donna Forsyth was a contributor to the document.