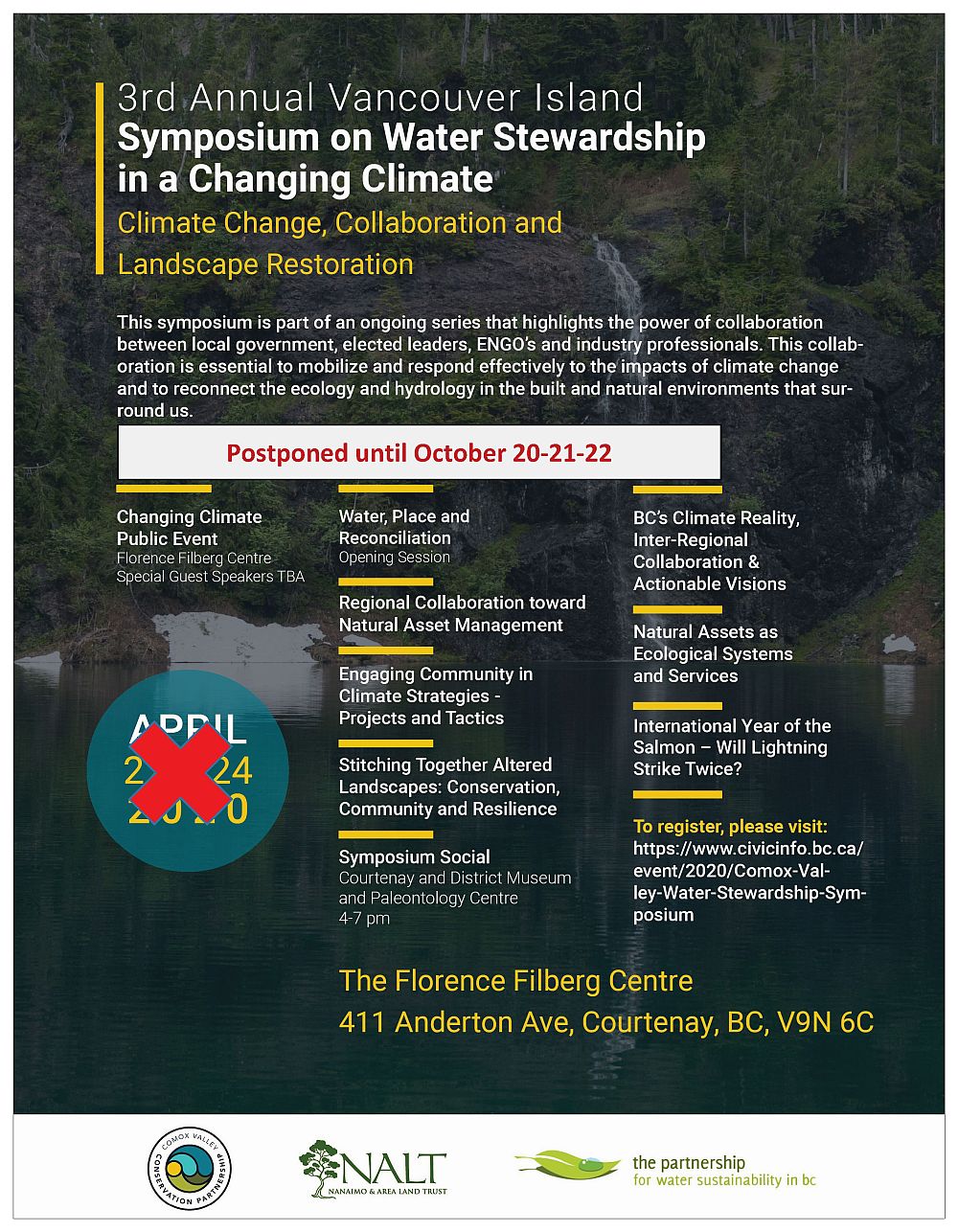

WATER, PLACE & RECONCILIATION IN BRITISH COLUMBIA: “Our vision is to transform an eco-liability into an eco-asset in the heart of the K’ómoks Estuary,” states Caila Holbrook, Project Watershed’s Manager of Fundraising, Outreach and Mapping (Announcement #7 in March 2020 for the Comox Valley 2020 Symposium – which was postponed and then reimagined due to COVID 19 pandemic)

Note to Reader:

Comox Valley Project Watershed Society (Project Watershed) in partnership with the K’ómoks First Nation and the City of Courtenay have embarked on an ambitious initiative to restore an abandoned industrial sawmill site to natural habitat.

Kus-kus-sum is an 8.3 acre, concrete-covered private property situated adjacent to the Courtenay River where it meets the K’ómoks Estuary in Courtenay, British Columbia. The aim is to restore the property to natural intertidal wetland habitat which is part of a larger ecosystem-based strategy to restore the K’ómoks Estuary.

Kus-kus-sum as it looked when then there was an operating sawmill for 50 years (photo credit: Dan Bowen)

Councillor Doug Hillian, City of Courtenay / Chief Nicole Rempel, K’ómoks First Nation / Paul Horgen, Project Watershed

Unpaving Paradise at Kus-kus-sum on the Courtenay River

The name Kus-kus-sum is attributed to the property by The K’ómoks First Nation in recognition of the traditional use of the site as a cemetery (tree-burials) associated with a village that was located directly across the river. This traditional use highlights the significance of the site to the Kómoks Nation.

Shortly after settlement the site was developed as a fruit and vegetable cannery, and later (1949) a saw mill. Over the next 50 years, to facilitate industrial sawmill operations, the area was cleared and paved and a steel-clad concrete retaining wall, which encroaches into the river, was erected along the shoreline.

These alterations effectively destroyed the fish and wildlife habitat values of the site. Seals have been observed using the steel wall to trap and prey upon both out-migrating juvenile and returning adult salmon, significantly affecting local salmon populations.

In the article below, Caila Holbrook paints a picture of the vision for transforming an eco-liability into an eco-asset.

Panorama of the steel-clad concrete retaining wall at the Kus-kus-site (photo credit: Richard Boyle)

Seal feasting on salmon along the Kus-kus-sum wall

Restoring Nature Builds Resilience

Before the Sawmill, there was a Properly Functioning Ecological System

“Estuaries are some of the most productive habitats on Earth and the K’omoks Estuary is a prime example of that. Based on its size, habitat, vegetation, water bird use, shellfish and fin-fish resources (including salmon and herring) the K’ómoks Estuary has been ranked a Class One estuary – a status only eight of the 442 estuaries in British Columbia have attained.

“Pre-1950 aerial photographs confirm that Kus-kus-sum was indeed a forested streamside area in the K’ómoks Estuary with side-channels connecting it to the adjacent Hollyhock Marsh. Habitats like this would have been common in the estuary building redundancy and resilience into this coastal area. They would have provided important resources for plants, fish, birds and other wildlife. Over 90% of tidally influenced wetland forest has been destroyed along the Pacific coast of North America. Now many of the species that require this habitat are considered species at risk.

Kus-kus-sum as it looks in 2020 prior to restoration

Restoring Kus-kus-sum is an 8.3 Acre Step in the Right Direction

”The restoration process will include removing built infrastructure from the site, removing fill, re-grading the topography of the area, planting native species and removing the steel wall. Nature will come back; it is already trying to – as trees and salt marsh plants are poking through the 1 foot deep rebar-reinforced concrete.

“Once acquired, a conservation covenant will be placed on the property to protect it in perpetuity. It will be connected to adjacent conservation lands providing species with access to hundreds of hectares of tidally-influenced habitat.

“In addition to Kus-kus-sum’s habitat values, it will function as part of the K’ómoks Estuary ecosystem helping filter water, regulate nutrients, sequester carbon, attenuate floodwaters and provide recreational and educational opportunities. It will also provide space for the shifting of land, sea and wildlife habitats associated with climate change.”

Keeping It Living

“In 2017, Project Watershed launched a fundraising campaign to purchase the land from Interfor Corporation, the current owners,” reports Caila Holbrook.

“The fundraising has been very successful and a variety of governments, community groups, local businesses and citizens have come together to support this initiative. However, Project Watershed still needs to raise $1 million to complete the acquisition by June 30th, 2020. We are accepting donations online at www.projectwatershed.ca.

“Once acquired, ownership of the land will be transferred to the K’ómoks First Nation and the City of Courtenay establishing an historic relationship between the two governments. The intent of which is to allow for the K’ómoks First Nation to build the capacity needed to become the sole landowners who maintain the property’s conservation values over time. After all, the plethora of First Nation fish traps dating back well over 1000 years in the K’ómoks Estuary substantiates the fact that First Peoples have been stewarding this land for generations.

“Through the restoration of Kus-kus-sum we can reconcile our past with our need to work together to build resilience in the face of global issues such as climate change and species extinction,” concludes Caila Holbrook.

Kus-kus-sum as it would look after proposed restoration (photo credit: Robert Lundquist)

Pre-1950, Kus-kus-sum was a forested streamside area, with side-channels connecting it to the adjacent Hollyhook Marsh (featured in the photo above).

THIS ARTICLE IS THE SEVENTH IN A SERIES

- Backgrounder #1- Comox Valley on Vancouver Island: Incubator Region for Collaboration Precedents (Answers the question – why hold the third in the symposia series in the Comox Valley?)

- Backgrounder #2 – Comox Valley Conservation Partnership – “One common forum to promote and advocate for innovative local government policies, strategies and initiatives that support transformative change towards environmental sustainability,” wrote David Stapley and Tim Ennis (Context for Day One Modules)

- Backgrounder #3 – FROM ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION TO SUSTAINABLE DELIVERY OF CORE SERVICES: “Natural assets support the delivery of core local government services, while doing so much more” (Module F on Day Two)

- Backgrounder #4 – An ‘Actionable Vision’ translates good intentions into practices on the ground: It’s driven by leadership that mobilizes people and partnerships, a commitment to ongoing learning and innovation, and a budget to back it up (Module E for Day Two)

- Backgrounder #5 – A ‘once in a generation’ window of opportunity: The International Year of the Salmon program has the potential to be a game-changer. It is not just about the fish; it is about humankind creating sustainable landscapes for people and salmon (Module G on Day Two) published on February 25, 2020

- Backgrounder #6 – Implementing Actionable Visions – Are you curious to learn what it means to collaborate to ‘stitch together altered landscapes‘, and thus improve where we live? (Synopsis for Day Two Program on Reconnecting Hydrology and Ecology) published on March 10, 2020

Water, Place and Reconciliation

What is the starting place for our work in water sustainability, landscape scale restoration, collaboration and facing the impacts of a changing climate? It starts with an understanding of the culture, land, water and stories of the places where we do our work.

On Day One, join us for this welcome to the territory of the K’omoks First Nation and an introduction to the exciting projects underway that demonstrate shared commitment.

The Kus-sum-sum project has attracted the attention of, and funding from, BC Premier John Horgan and his provincial government cabinet. Could Kus-sum-sum restoration be a catalyst for a program of stitching together, over time, other altered landscapes in the Comox Valley and beyond?

TO LEARN MORE:

THE PROGRAM HAS 7 MODULES. IF YOU WISH TO LEARN MORE ABOUT EACH, CLICK ON THE LINK TO DOWNLOAD THE COMOX VALLEY 2020 PROGRAM BROCHURE

Visit the Symposium homepage on the waterbucket.ca website.to learn much, much more about the “stories behind the stories”.

ON DAY ONE, delegates will learn about what is happening on the ground to restore ecosystems and build resiliency to climate change in the Comox Valley. Actions and tools that build collaborative working relations between the stewardship, First Nations and local government sectors will be highlighted.