Beyond the Guidebook 2015: Look at a Watershed as a Whole System.…

Note to Reader:

Released in November 2015, Beyond the Guidebook 2015: Sustainable Watershed Systems, through Asset Management is structured as a “front-end” plus four parts to meet the information needs of different audiences. The “front-end” presents three theme areas in order to provide the reader with an over-arching context before delving into the details in the four parts. The three theme areas are:

- The Shifting Baseline Syndrome

- Why Beyond the Guidebook 2015

- Look at a Watershed as a Whole System

This second of three posts is the extract that explains why it is necessary to Look at a Watershed as a Whole System.

Hydrology-Based Framework for Action

Watershed protection starts with an understanding of how water gets to a stream from individual sites, how long it takes, and whether there are impacts along the way.

The pioneer work of Horner and May provided a reason and a starting point for revisiting urban hydrology in BC. This resulted in development of the Water Balance Methodology to link actions at the site scale with outcomes at a watershed scale.

“So many studies manipulate a single variable out of context with the whole and its many additional variables,” states Dr. Richard Horner, now an adjunct professor at the University of Washington. “We, on the other hand, investigated whole systems in place, tying together measures of the landscape, stream habitat and aquatic life.”

“So many studies manipulate a single variable out of context with the whole and its many additional variables,” states Dr. Richard Horner, now an adjunct professor at the University of Washington. “We, on the other hand, investigated whole systems in place, tying together measures of the landscape, stream habitat and aquatic life.”

The work of Horner and May is standing the test of time. The reason is that they applied systems thinking and looked at watersheds as a whole.

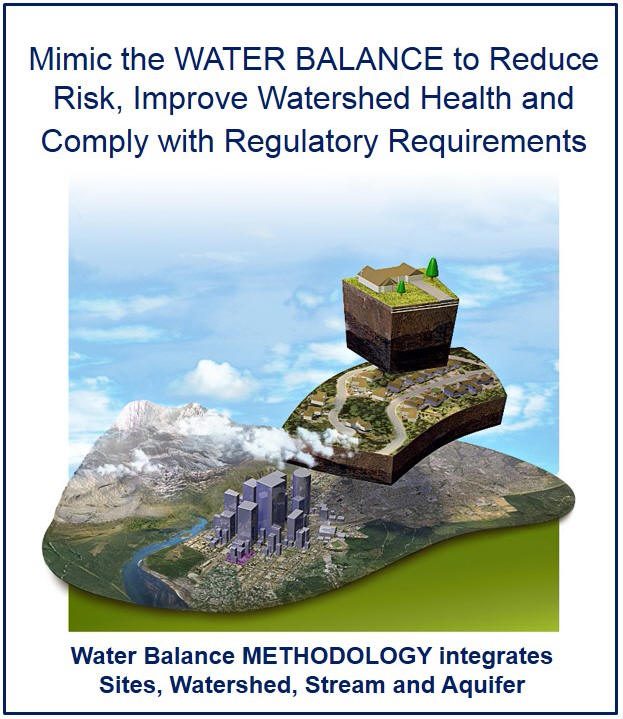

Water Balance Methodology

“The need to protect headwater streams in BC has forced us to expand our view from one that looks at the site by itself, to one that considers the site, watershed, stream and aquifer as an integrated system,” states Jim Dumont, Engineering Authority for the Partnership for Water Sustainability in BC. “The Water Balance Methodology addresses flow path differences, and provides solutions that would maintain stream health within a developed watershed.”

“The need to protect headwater streams in BC has forced us to expand our view from one that looks at the site by itself, to one that considers the site, watershed, stream and aquifer as an integrated system,” states Jim Dumont, Engineering Authority for the Partnership for Water Sustainability in BC. “The Water Balance Methodology addresses flow path differences, and provides solutions that would maintain stream health within a developed watershed.”

Altering the Water Balance Distribution has Wet-Weather Consequences: Increasing Surface Volume + Longer Flow Duration = More Stream Erosion + Loss of Stream Habitat

Adaptation to a Changing Climate: The climate in BC is changing: wetter, warmer winters: longer, drier summers. It is necessary to mimic the Water Balance to ensure water supply in dry weather and prevent drainage impacts in wet weather.

- Warmer winters mean more rain, less snow. Thus, there will be less flow to sustain creeks and satisfy water needs during the dry months.

- Intensified land development hardens the land and short-circuits the Water Balance. When it rains, there is more drainage from urban areas.

- More flow results in stream erosion, channel blockages, streams jumping their banks, damage to aquatic habitat and risk to salmon.

- Consequences include expensive fixes at a time when communities are challenged to fund and replace essential infrastructure services.

Now that BC’s climate is changing, the ‘changes in hydrology’ driver for aquatic habitat protection in tributary streams will ultimately benefit people too.

Implementing ‘design with nature’ standards of practice at the site scale – so that benefits accumulate and mimic the natural Water Balance at a watershed scale – ultimately means that communities will be more resilient during periods when there is either too much or too little.

To Learn More:

The Primer on Water Balance Methodology for Protecting Watershed Health is the fifth in a series of guidance documents that form the basis for knowledge-transfer via the Georgia Basin Inter-Regional Education Initiative (IREI). The foundation document for the series is Stormwater Planning: A Guidebook for British Columbia, released in 2002.