Story #1 in the ISMP Course Correction Series: Re-Focus on Stream Health and Watershed Outcomes

Note to Readers:

This article is the first in a series that is designed to inform local governments and others about Integrated Stormwater Management Plans (ISMPs): what they are; how local governments can do more with less; and how local governments can ensure ISMPs are outcome-oriented.

An ISMP is a potentially powerful tool to achieve a vision for ‘green’ development, one that protects stream health, fish habitat and fish. Local governments now have a decade of experience from which to extract lessons learned.

Local government experience in Metro Vancouver and on Vancouver Island has informed the ‘ISMP course correction’ described in Beyond the Guidebook 2010: Implementing a New Culture for Watershed Protection and Restoration in British Columbia.

Story #1 provides regulatory and historical context, identifies introduces guiding principles for implementing change on the ground, explains what outcome-oriented means, and sets the stage for the four stories that will follow in the coming weeks. To download a PDF version, click on Integrated Rainwater Management Planning: Re-Focus on Stream Health and Watershed Outcomes

Historical / Regulatory Context for ISMPs

Use of the ISMP term is unique to British Columbia. First used by the City of Kelowna in 1998, the term quickly gained widespread acceptance by local governments and environmental agencies to describe a comprehensive approach to watershed-based planning in an urban context.

The Province recognizes that communities are in the best position to develop solutions which meet their own unique needs and local conditions. Historically, then, the Province has enabled local government by providing policy and legal tools in response to requests from local government. The enabling approach means the onus is on local government to align local actions with provincial and regional policies, and embrace shared responsibility.

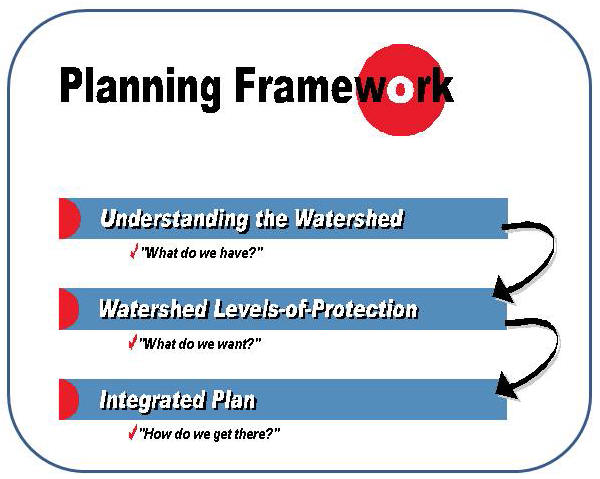

Plan at Four Scales – Regional, Watershed, Neighbourhood and Site

When the Province released Stormwater Planning: A Guidebook for British Columbia in June 2002, the ISMP approach became a recognized provincial process. Although Integrated Watershed Management Plan better described what was envisioned at that time, use of IWMP was not an option because the Province had an existing IWMP process for natural resource management in wilderness watersheds.

In 2002, the Guidebook introduced a set of five guiding principles for ISMPs (scroll down to view image). These are captured by the acronym ADAPT, where the “P” stands for Plan at four scales – regional, watershed, neighbourhood and site.

“In integrating actions at four scales, the intended purpose of an ISMP is to provide a clear picture of how local governments can be proactive in applying land use planning tools to protect property and aquatic habitat, while at the same time accommodating land development and population growth,” states Peter Law, Chair of the Guidebook Steering Committee (2000 -2002).

“In integrating actions at four scales, the intended purpose of an ISMP is to provide a clear picture of how local governments can be proactive in applying land use planning tools to protect property and aquatic habitat, while at the same time accommodating land development and population growth,” states Peter Law, Chair of the Guidebook Steering Committee (2000 -2002).

Manage Runoff Volume at Site Scale to Protect Watershed Health

In Beyond the Guidebook 2010, the term ‘urban watershed’ is a metaphor for those watersheds, or parts of watersheds, over which local governments exert control through regulation of land use. The Community Charter empowers British Columbia municipalities with extensive and very specific tools to proactively manage the complete spectrum of rainfall events.

In addition, British Columbia case law makes clear the responsibility of municipalities to manage runoff volume to prevent downstream impacts. An increasingly important corollary to that responsibility is the need to work from the regional down to the site scale, to maintain and advance watershed health to ensure that both water quantity and quality will be sustained to meet both ecosystem and human health needs.

Living Water Smart, British Columbia’s Water Plan

Released in June 2008, Living Water Smart, British Columbia’s Water Plan provides a clear statement of provincial policy vis-à-vis how land will be developed and water will be used. Furthermore, the 45 actions and targets in Living Water Smart encourage ‘green choices’ that will flow through time, and will be cumulative in creating liveable communities, reducing wasteful water use, and protecting stream health.

The Water Sustainability Action Plan for British Columbia is aligned with Living Water Smart, and is a primary implementation interface with local government. The Action Plan program is providing engineers and planners in a local government setting with tools to effect changes in land development, infrastructure servicing and water use practices. The program is also showcasing what local government implementers are doing on the ground.

Success Will Follow When….

Beyond the Guidebook 2010 tells the stories of the champions who are implementing change on the ground. Equally important, this guidance document also presents a framework for establishing watershed-specific performance targets and implementing green infrastructure through an ISMP-type process.

Lessons Learned

There is now a decade of ISMP and comparable experience from which to extract ‘lessons learned’ about how to move from awareness (interest) to action (practice). . Beyond the Guidebook 2010 draws on BC case study experience to illustrate how success will follow when local government elected representatives, administrators and practitioners apply these guiding principles:

- Choose to be enabled.

- Establish high expectations.

- Embrace a shared vision.

- Collaborate as a ‘regional team’.

- Align and integrate efforts.

- Celebrate innovation.

- Connect with community advocates.

- Develop local government talent.

- Promote shared responsibility.

- Change the land ethic for the better.

The Bowker Creek Blueprint is a prominent example of a plan that embodies all ten guiding principles, and is precedent-setting in advancing an outcome-oriented approach. The Bowker Creek Blueprint is about systematically restoring the urban heartland of the Capital Regional District as it redevelops over the decades. The Bowker experience illustrates how major breakthroughs happen when decision makers in government collaborate with grass-roots visionaries in the community to create desired outcomes.

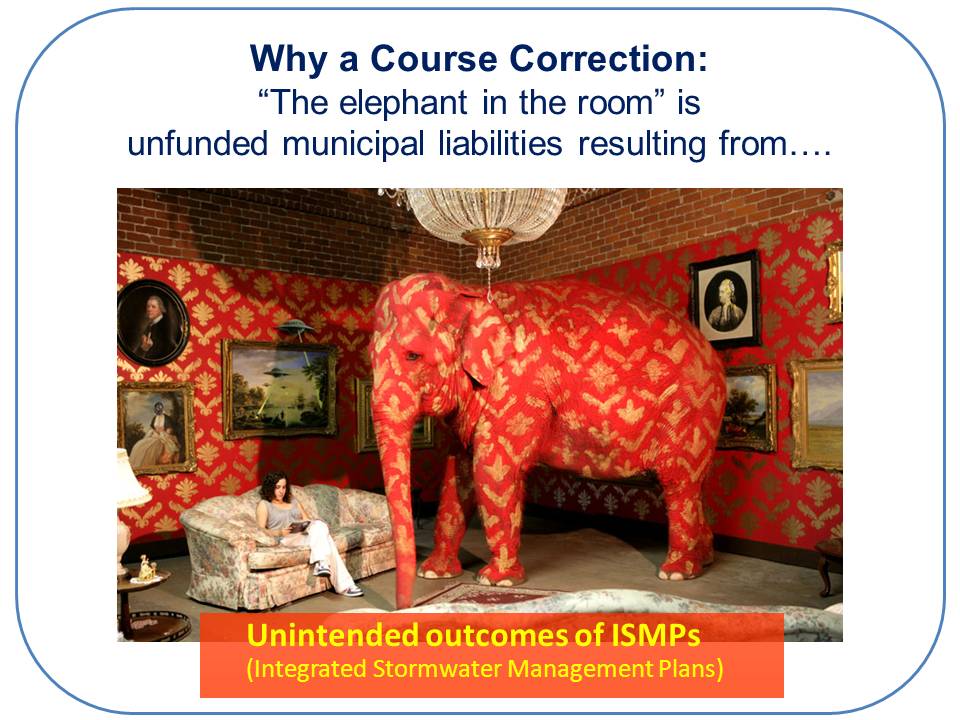

The Elephant in the Room

The elephant in the room is always money. Municipalities have lots of competing interests for spending money; lots of projects to keep staff busy; and finite financial resources. Everyone is challenged to do more with less and get it done. An issue that has emerged on both sides of the Georgia Basin is ‘cost versus value’ in developing ISMPs.

The unintended consequences of some ISMPs undertaken in Metro Vancouver and on Vancouver Island have informed the course correction described in Beyond the Guidebook 2010. “Unfortunately, ISMPs completed to date have tended to be engineering-centric, and in general can be described as ‘glorified’ master drainage plans. ISMPs that do not integrate land use and drainage planning are resulting in unaffordable multi-million dollar infrastructure budget items that become municipal liabilities, without providing offsetting stream health benefits,” stated the Metro Vancouver Liquid Waste Management Plan Reference Panel in its Final Report to the Metro Vancouver Board in July 2009.

This finding led the Reference Panel to recommend that Metro Vancouver municipalities “re-focus Integrated RAINwater/Stormwater Management Plans on watershed targets and outcomes so that there are clear linkages with the land use planning and development approval process.”

What ‘Outcome-Oriented’ Means

Outcome-oriented planning is a problem-solving PROCESS. It is not a procedure. It is not a matter of applying a regulation or a checklist. Going through a process becomes talent development. Participants have to be committed to the outcome. To get there, they have to function as a team. It is the talent development process that enables development of outcome-oriented plans. It is very definitely a grounded approach.

Focus on Values and Actions

Experience has demonstrated that four ingredients will be in the mix when practitioners in a local government setting undertake to develop outcome-oriented plans. The participants will have to collaborate to:

- Define the problem

- Declare the community’s values

- Select and apply the right tools

- Wrestle with the solutions

This is not high-level or theoretical language. It is about hard work and applying common sense. Mutual support and the shared process are also critical. This is what has been learned from successful outcome-oriented processes such as the Bowker Creek Blueprint. Focus on values and actions. Keep it simple. Find a starting point that is intuitive to everyone. Ensure actions are practical and easy to implement.

Looking Ahead

The Guidebook is a pioneer application in North America of ‘adaptive management’ in a rainwater management setting. In fact, this is one of the five guiding principles for ISMPs. In the Guidebook, adaptive management means: We change direction when the science leads us to a better way.

Leading Change in British Columbia

After a decade of ‘learning by doing’, it is now timely to reflect on the experience of those local governments that are leading change in British Columbia. Accordingly, themes for upcoming stories in the ISMP Course Correction Series are previewed as follows:

- Story #2: Capitalize On Green Infrastructure Opportunities to ‘Design with Nature’

- Story #3: Apply a Knowledge-Based Approach to Focus on Solutions and Outcomes

- Story #4: Move to a Levels-of-Protection Approach to Sustainable Service Delivery

- Story #5: Apply Inexpensive Screening Tools to ‘Do More With Less’

The case study experience introduced in Beyond the Guidebook 2010 shows that a new land ethic is taking root in BC. Changing the culture requires a process. This takes time to complete. There is no short-cut; however, lessons learned by those who have done it can help those who want to do it.

Posted November 2010