DESIGN WITH NATURE TO CREATE LIVEABLE COMMUNITIES AND PROTECT STREAM HEALTH: “There was tension between stakeholders. Yet the productiveness of those dialogues inspired a lot of professionals, myself included, to dig deeper and find solutions and learn. You felt like you were part of a movement,” recalled Susan Haid, career environmental and urban planner in BC local government

Note to Reader:

Published by the Partnership for Water Sustainability in British Columbia, Waterbucket eNews celebrates the leadership of individuals and organizations who are guided by the Living Water Smart vision. Storylines accommodate a range of reader attention spans. Read the headline and move on, or take the time to delve deeper – it is your choice! Downloadable versions are available at Living Water Smart in British Columbia: The Series.

The edition published on April 2, 2024 featured Susan Haid. She has played a leadership role in trailblazing an ecosystem-based approach to community planning in British Columbia. This approach flowed from passage of the Fish Protection Act 1997. Transformational in nature, it spawned an array of initiatives. The need for this approach to land-use planning is ever more important today.

Policy frameworks to shape urban design

Susan Haid has played a leadership role in trailblazing an ecosystem-based approach to community planning in British Columbia, first with the City of Burnaby and then with Metro Vancouver. This approach also took root in her subsequent experience in the District of North Vancouver and the City of Vancouver.

She joined Burnaby in 1993 a year after the city created the first environmental planner position in the region. At Metro Vancouver, Susan Haid worked to shift perspectives to a regional scale.

When she retired from local government in 2022, Susan Haid was Deputy Director of Planning with the City of Vancouver. Currently, she is an instructor in UBC School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture for urban design as public policy.

Susan Haid offers valuable insights that illuminate the story behind the story of the Fish Protection Act 1997. This “watershed moment” in BC history launched the ecosystem-based approach, also known as the watershed-based approach, as a provincial policy and legislative outcome. The need for this approach to land-use planning is ever more important today.

Historical context for the goal of making fish protection and streamside regulation work

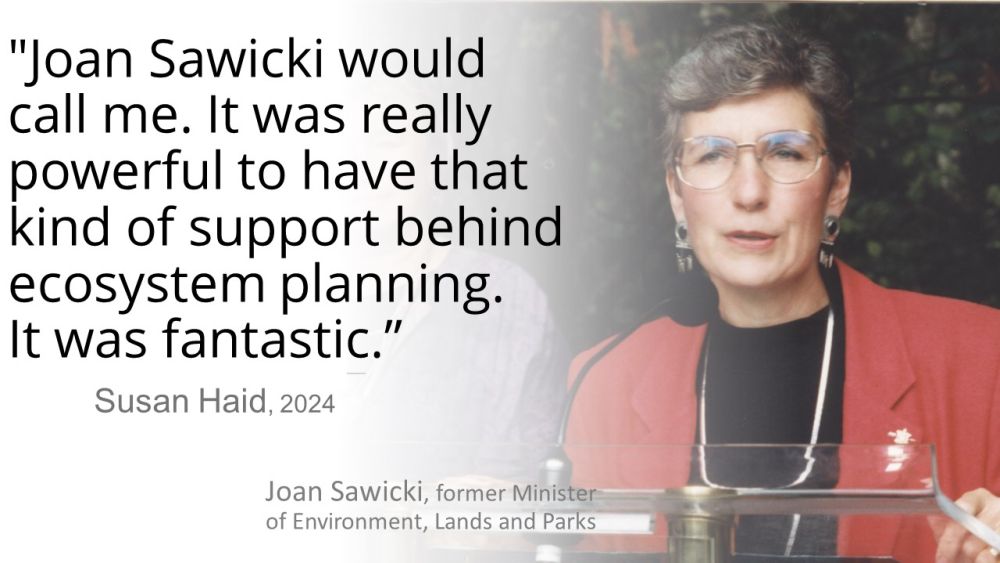

“In late 1996, in came Erik Karlsen from the Province as the spokesperson for the first Fish Protection Act. He convened discussions with environmental, engineering and planning staff,” Susan Haid recalls.

“Those were such fantastic discussions and collegiality between municipalities. There was a really good alignment and call to action on making streamside regulation work.”

“It was a major advancement but a lot of stress as well. Streamside regulation was being portrayed as a huge land grab. There was a lot of back and forth to move from something that was site-specific to more of a hardline edict with the province.”

“The 1990s was a very instrumental time of policy and regulation development. And municipal dialogue too.”

EDITOR’S PERSPECTIVE / CONTEXT FOR BUSY READER

“A terrific Steve Jobs quote encapsulates why processes and outcomes go awry when there is a ‘don’t know, don’t care’ mindset about the history behind the WHY and HOW of policy frameworks that shape urban design,” stated Kim Stephens, Waterbucket eNews Editor and Partnership Executive Director.

“Further, Steve Jobs explained that dot-connectors ‘have had more experiences or they have thought more about their experiences than other people’.”

“It is unfortunate, he added, that ‘a lot of people haven’t had very diverse experiences’ which is why they are ‘without a broad perspective on the problem’. This results in missed opportunities to learn from and build upon the innovation and experience of others.”

Connecting dots to chart a course

“BC communities are experiencing the unintended environmental consequences of policy frameworks that have not been well implemented. But despair not. Knowledge and wisdom that would pull us back from the brink are waiting to be rediscovered and mobilized so that communities can change course in time.”

“My conversations with Susan Haid and other thought leaders shed light on ‘dots’ that would inform a mindset change. However, wanting to know what dots to connect would be the prelude to an attitude switch by practitioners and decision makers that triggers a course correction. ”

Fish Protection Act spawned an array of initiatives

“Charting a course through perilous waters starts with understanding WHY certain ‘dots’ from the period 1997 through 2005 are foundational.”

“The Fish Protection Act 1997 is one such dot. Yet this rich history may be largely ignored and/or forgotten. Reconnecting with this experience can help illuminate the current path forward.”

“Passage of the Fish Protection Act 1997 was the culmination of an attitude switch in response to the salmon crisis of the 1990s. Transformational in nature, it spawned the Riparian Areas Protection Regulation (RAPR), Stormwater Planning: A Guidebook for British Columbia, Integrated Stormwater Management Plans (ISMPs), and the Partnership for Water Sustainability.”

“Unfortunately, RAPR was not well-implemented and that undermined good intentions. In response to scathing critiques in a series of reports by the Ombudsperson between 2014 and 2022, the current provincial government is working to reinvigorate riparian enforcement.”

“The Ombudsperson’s 2014 investigation identified ‘significant gaps between the process the provincial government had established when RAPR was enacted and the level of oversight that was actually in place’.”

“The 2022 update states that ‘many of the issues we identified remain as pressing as they were in 2014; there is work ahead to ensure that the systemic issues are fully addressed’,” concluded Kim Stephens.

Ecosystem-based approach is needed more than ever to adapt to weather extremes

“It is really heartening to observe the recent renewed interest in what I think of as ecosystem-based planning and is now often called green and blue systems in cities,” states Susan Haid.

“It sounds simple, but it is heartening because this has NOT really been a key theme in the public dialogue for some time. The pandemic has reminded us of the importance of green space and access to nature.”

“It is even more important now because in 1997 we did not have the kind of weather extremes such as atmospheric rivers and heat domes we are now regularly experiencing.”

“There is a resurgence of ideas that is influencing policy making!”

STORY BEHIND THE STORY: Policy frameworks to shape urban design – extracts from a conversation with Susan Haid

“Concepts of mentorship and reflecting real-world examples are things that I really espouse in teaching. But I also find that it is an opportunity for me to learn and to continue growing,” says Susan Haid.

“In many ways, what I am teaching comes back to the same kind of framework around ecosystem-based planning which Erik Karlsen and others were advancing in the 1990s, and which is synonymous with watershed-based planning.”

SHARPENING THE EDGE: Policy framework for a sustainable and resilient Salish Sea region

“Since January 2023, I have been teaching a master level course in urban design policy at UBC. Titled Policy for a Sustainable Region, it is big picture and is about policy frameworks to influence urban design.”

“A lot of it is case studies and reflection. But I also bring in resiliency and ecological frameworks, with lectures on what are the best practices going forward. I call these sessions SHARPENING THE EDGE.”

“By that I mean here are the provincial, regional and local frameworks and what you do at the site level. But then there is sharpening the edge through emergent sustainable development practices and looking at them through a lens of resiliency, equity and reconciliation.”

Resurgence of interest in application of ecosystem-based principles to city planning

“Maybe it is because my first post-secondary education was in biology and ecology that I align strongly with an ecosystem-based approach to planning.”

“The principles of diversity, interconnectivity, and redundancy within a systems approach are very robust and stand the test of time. I believe these principles are ever more important.”

“Watershed-based planning builds on these principles and can support everything from access to nature, wellbeing, mental health to green infrastructure, stewardship, equity and reconciliation.”

|

|

|

“There was such great work happening in the mid-1990s. There was an early draft of an Environmentally Sensitive Areas strategy. And Burnaby had one of the early interagency Environmental Review Committees in the region.”

“Then, in late 1996, in came Erik Karlsen. He was the secret sauce who convened the fantastic streamside regulation discussions that created collegiality between municipalities.”

“There was tension between stakeholders. Yet the productiveness of those dialogues inspired a lot of professionals, me included, to dig deeper and find solutions and learn. You felt like you were part of a movement.”

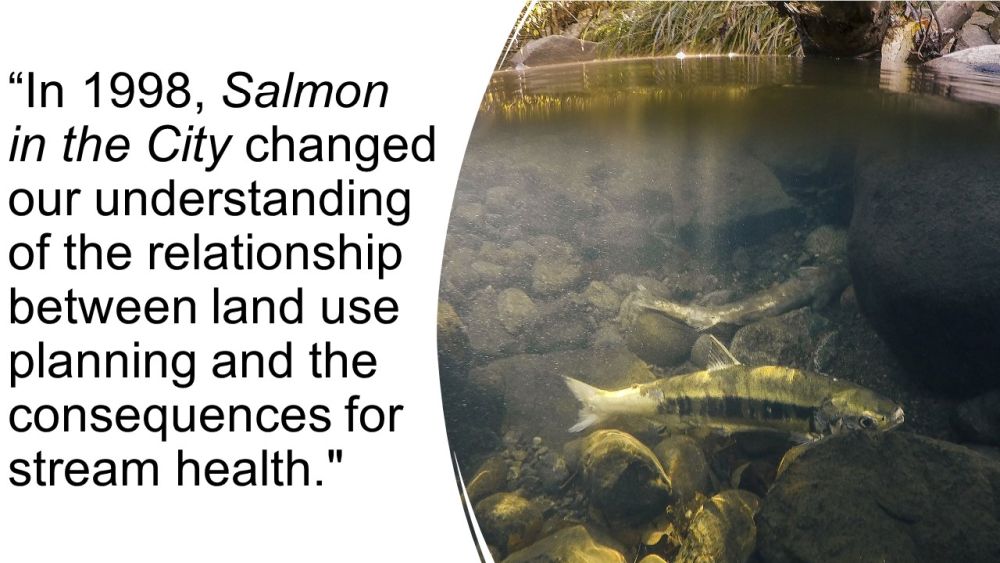

“As I reflect on my career in local government, there has been a lot of learning that has raised awareness and driven changes in land planning practice. A defining moment for me was the Salmon in the City Conference in 1998. It was a memorable event.”

|

“The work that was going on at that time took a watershed-based approach to a regional scale. There was some really rigorous watershed evaluation from a biological perspective. And there was such great work happening in collaboration with groups such as the one led by UBC’s Hans Schreier.”

“We had a Biodiversity Strategy Working Group. And with our engineering colleagues, we also had the development of the ISMP framework within the region’s Liquid Waste Management Plan. In short, these layers of watershed-based planning were happening concurrently.”

“The Fish Protection Act enabled local governments to shift from site-by-site fights with developers over setback requirements…to a regional scale tool and a prioritization of ISMPs based on ecological value.”

Making a difference was exciting for all involved

“It was not like it was rocket science. But the fact that it actually came together at a regional scale with partnerships, and across planning and engineering and parks portfolios, was pretty exciting for everyone involved.”

“You really felt like you were making a difference in terms of guiding ecologically functioning development and growth management.”

“Overall, the work that we were all doing at the time had that strong ecological framework aspect to it. And that is what stands out in my mind for the period 1997 through 2005, Seeing how these foundations are being built upon and advanced rekindles my optimism for the future,” concludes Susan Haid.

Living Water Smart in British Columbia Series

To download a copy of the foregoing resource as a PDF document for your records and/or sharing, click on Living Water Smart in British Columbia: Policy frameworks to shape urban design.