TURNING IDEAS INTO ACTION: “I believe that engineers need to move away from a technocentric approach and adopt a sociotechnical mindset. By this I mean we need to start thinking about the ways in which the social and technical are always connected. These aspects should not be separated, with technical challenges going to the engineers and social challenges going to the sociologists,” stated Professor Gordon Hoople, University of San Diego (January 2022)

Note to Reader:

This article by Gordon D. Hoople, Assistant Professor of Engineering at the University of San Diego, is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. Professor Hoople one of the founding faculty members of integrated engineering at the University of San Diego. He is passionate about creating engaging experiences for his students. His work is primarily focused on two areas: engineering education and design. In his education research, Professor Hoople focuses on developing pedagogies that help students develop a critical understanding of the ways in which engineers impact society.

Future engineers need to understand their work’s human impact – here’s how my classes prepare students to tackle problems like climate change

Engineers spend much of their time absorbed in the technical aspects of problems, whether they’re designing the next generation of smartphones or building a subway.

As recent news stories attest, this technocentric approach has some critical limitations, and the result can end up harming rather than helping society.

For example, artificial intelligence algorithms designed by software engineers to promote user engagement turn out to undermine democracy and promote hate speech. Pulse oximeters, key tools in diagnosing COVID-19, work better on light skin than dark. Power plants and engines, which have enabled much of the “progress” seen since the Industrial Revolution, have fueled climate change.

As an engineering professor, I have spent the past six years trying to figure out how to educate the next generation of engineers to avoid these mistakes.

Research shows that one of the key problems is that engineering classes often focus on decontextualized problems, failing to take into account the social context. We ask students to spend far too much time solving mathematical equations and far too little time thinking about the human dimensions of the problems they are trying to solve.

Practicing engineers are called on to solve ill-posed, messy problems that do not have one correct answer that’s easily found in a textbook. Students need the opportunity to confront, rather than avoid, this complexity during these crucial formative years when they learn to think like engineers.

Engineering classes at the University of San Diego have started integrating discussions of the social impact of technology like drones. Gordon Hoople

Engineering classes at the University of San Diego have started integrating discussions of the social impact of technology like drones. Gordon Hoople

Engineering schools began focusing almost exclusively on science and math during the Cold War.

Engineering schools began focusing almost exclusively on science and math during the Cold War.

Fox Photos via Getty Images

The Cold War influence that lingers today

Most engineering programs focus on standard “engineering science” courses, such as statics, thermodynamics and circuits, that trace their influences back to the technological race with the former Soviet Union during the Cold War, as Jon Leydens and Juan Lucena explain in their book Engineering for Justice.

It was then – some seven decades ago – that engineering curriculums began to emphasize the scientific and mathematical basis of engineering, cutting back on hands-on engineering design and humanities courses. While most engineering programs now incorporate these types of courses, engineering classes themselves still often have a persistent divide between the social and technical.

Even more disheartening, my colleague Erin Cech’s work on the “culture of disengagement” found that engineering students seemed to graduate from college more disengaged from social issues than when they started.

In a longitudinal survey of students across four universities, she found that students’ commitment to public welfare declined significantly over the course of their engineering education. The study, published in 2013, surveyed 326 students each year during college as well as 18 months post-graduation. She found that students’ “beliefs in the importance of professional and ethical responsibilities, understanding the consequences of technology, understanding how people use machines, and social consciousness all decline.”

Far from improving students’ ability to engage on these critical issues when they graduate, the traditional approach may be making things worse. Some schools have changed their approach in recent years, but many have not.

Many elements of engineering have social impacts, particularly discussions of energy and climate change.

Many elements of engineering have social impacts, particularly discussions of energy and climate change.

leventince via Getty Images

How I’m encouraging a ‘sociotechnical’ mindset

I believe that engineers need to move away from a technocentric approach and adopt a sociotechnical mindset, as I explain in my book Drones for Good: How to Bring Sociotechnical Thinking into the Classroom. By this I mean we need to start thinking about the ways in which the social and technical are always connected. These aspects should not be separated, with technical challenges going to the engineers and social challenges going to the sociologists.

Sociotechnical thinking is the capacity to identify this relationship and to solve problems with this relationship in mind.

In order to validate this approach to education, my colleagues and I have extensively studied the impact of sociotechnical thinking on student performance in a wide range of classes and contexts, including courses in energy, drones and design. Most recently, with funding from the National Science Foundation, we developed a new course, Integrated Approach to Energy, that integrated sociotechnical thinking from the first day.

We begin the semester not with the fundamental laws of thermodynamics, but instead with a practical conversation about how people actually use energy. As the semester progresses, we examine not only the technical intricacies of solar and wind, but also the ways in which fossil fuels have profoundly damaged our world.

Our peer-reviewed research on this class – conducted through interviews and analysis of students’ work and behavior – has shown that with a sociotechnical approach students maintain a high level of technical achievement but also develop awareness of the social implications of engineering practice.

Cautious optimism for the future

The field of education is notoriously resistant to change, and engineering education is no exception. As I write this, however, there is room for cautious optimism.

College students today are part of a generation that has turned the tide on years of declining civic engagement. Young leaders like climate activists Greta Thunberg and Leah Thomas have begun to call a powerful older generation to account.

This transformative mindset has made its way into the engineering classroom. College students are increasingly ready for conversations about the ways engineers can promote a sustainable future or engage with issues of social justice.

Several new engineering programs, including the department of integrated engineering at the University of San Diego, where I teach, and engineering, design and society at the Colorado School of Mines, are making sociotechnical thinking central to their curriculum. Other engineering schools, like Harvey Mudd, Smith and Olin, require their students to take a substantial number of humanities and social science courses and have made hands-on learning central to their curriculum.

In my view, the broad lesson is that it’s not enough to think society is one thing and technology is another. Anyone with a social media account can tell you it’s not that simple.

CALL TO ACTION: Move away from a technocentric approach and adopt a sociotechnical mindset

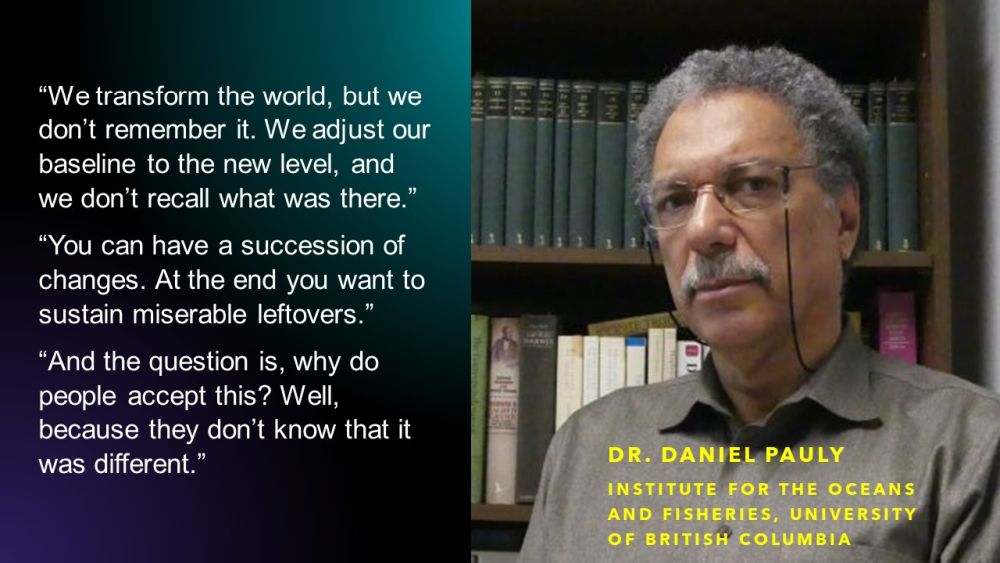

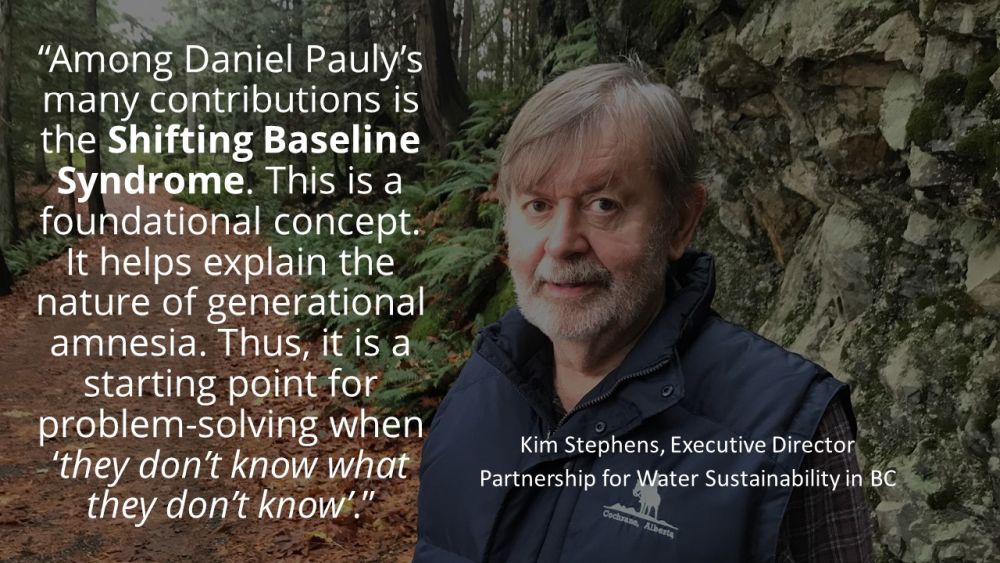

The edition of Waterbucket eNews published on November 9, 2021 featured Daniel Pauly’s Shifting Baselines Syndrome. The article is relevant to the conversation about engineering education and the need to move away from a technocentric approach and adopt a sociotechnical mindset.

In 1995, UBC Professor Daniel Pauly coined the term Shifting Baseline Syndrome to explain why and how ecological decline is incremental and imperceptible over multiple generations. In a 2003 interview, the NY Times described Daniel Pauly as “an iconoclastic fisheries scientist at the University of British Columbia who is so decidedly global in his life and outlook that he is nearly a man without a country”.

In September 2021, Greystone Books published The Ocean’s Whistleblower. It is the first authorized biography of Daniel Pauly, a truly remarkable man. Daniel Pauly is a living legend in the world of marine biology. He is also a man whose life has been shaped by struggle. And he lives in British Columbia.

Know Your History and Context to Offset Generational Amnesia

“To know where you are going, you need to know where you have come from. Otherwise, as Daniel Pauly observed in 1995 when he published a short-but-influential paper, baselines shift when successive generations of practitioners do not have an image in their minds of the recent past. Know your history. Know your context. These are keys to overcoming generational and organizational amnesia,” wrote Kim Stephens, Waterbucket eNews Editor and Executive Director, the Partnership for Water Sustainability in British Columbia.

“When the Partnership delivered a National Rainwater Management Workshop Series in 2014, referencing the Shifting Baseline Syndrome helped us explain to our audiences (in Calgary, Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal and Halifax) why we think differently in British Columbia. Because we do! How we think in this province is shaped by our topography and geography.”

“When we travelled across the continent, we realized just how crucial the stewardship ethic is in British Columbia. Yet, British Columbians as a whole may only be a generation or two away from becoming disconnected from nature. This means we are in a race against time to inspire an intergenerational collaboration ethic in the local government setting. This is the intergenerational mission of the Partnership.”

“As Daniel Pauly said during his TED Talk in 2010, we can recreate the past. Seeing examples of what the past looked like enables people to re-set their baseline, he stated. In BC, a learn-by-doing process is opening minds and building confidence that we can re-set the baseline. For the champions in many regions, the journey to date is decades-long. It is hard work. Yet there is hope. And that is why Waterbucket eNews celebrates and showcases those who are beacons of inspiration.”

TO LEARN MORE:

To read the complete story published on November 9th 2021, download a PDF copy of Living Water Smart: Know Your History and Context to Offset Generational Amnesia.