“The mottos of the sponge city are: Retain, adapt, slow down and reuse,” stated Kongjian Yu, the landscape architect who has transformed some of China’s most industrialized cities into standard bearers of green architecture

Note to Reader:

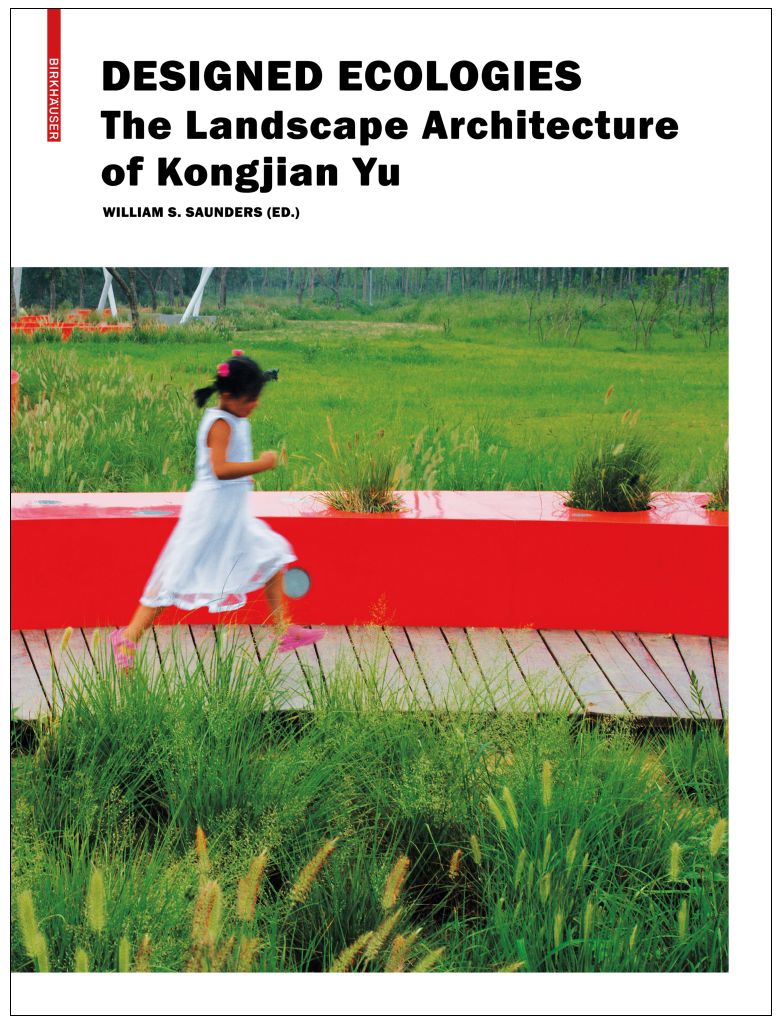

Generally recognized as one of the world’s leading landscape architects, Kongjian Yu is famous for being the man who reintroduced ancient Chinese water systems to modern design. He is best known for his “sponge cities”. President Xi Jinping and his government have adopted sponge cities as an urban planning and eco-city template.

He is professor of urban and regional planning, and founder and dean of the Graduate School of Landscape Architecture, at PekingUniversity. He received his Doctor of Design degree at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in 1995.

Professor Yu has been keynote speaker for three International Federation of Landscape Architects world congresses and two ASLA annual conferences, and has been invited to lecture and design critique at more than 30 universities worldwide, and is visiting professor of landscape architecture and urban planning and design at Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Chinese ‘Sponge Cities’ Capture Rainwater to Restore Urban Water Balance

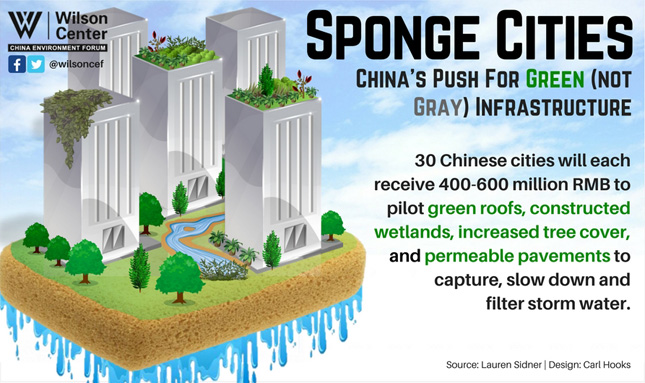

In 2013, at China’s Central Government Conference on Urbanization, President Xi Jinping injected a new term into the global urban design vocabulary when he proclaimed that cities should “act like sponges” and launched China’s Sponge City program. His proclamation came with substantial funding to experiment with ways cities can absorb precipitation.

Germany:

And then, in August 2017, the Senate of Berlin released its Sponge City Strategy. It is designed to tackle two issues – heat and flooding – by imitating nature and capturing rainwater where it falls.

“During the past 12 years we made quite good progress to install the ‘sponge-city concept’ or ‘decentralized stormwater management’ as we call it in Germany in the daily planning process,” states Dr. Heiko Sieker, urban hydologist.

United States:

Meanwhile, the City of Philadelphia is in Year 7 of a 25-year program to implement its Green City, Clean Waters program to create a citywide mosaic of green infrastructure and restore the water balance. Howard Neukrug fundamentally changed Philadelphia’s relationship with nature.

“Changing the world—or even one small piece of it—requires a lot of trial and error. We divide the city into communities, needs, types, gradients, opportunities, public, private and quasi-government,” stated Howard Neukrug.

Turning Cities into Sponges: How Chinese Ancient Wisdom is Taking on Climate Change

As an outcome of reintroducing ancient Chinese water systems to modern design, Kongjian Yu has transformed some of China’s most industrialized cities into standard bearers of green architecture. Yu’s designs aim to build resilience in cities faced with rising sea levels, droughts, floods and so-called “once in a lifetime” storms.

“In order to increase the resilience of a natural system, it is important to find solutions beyond the level of the city and even nation. I’m talking about a whole global system, in which we think globally but must act locally,” states Kongjian Yu.

“In order to increase the resilience of a natural system, it is important to find solutions beyond the level of the city and even nation. I’m talking about a whole global system, in which we think globally but must act locally,” states Kongjian Yu.

“And at this local scale we have design, which is a meeting point between technology and art where Western systematic thinking is grafted together with traditional Chinese wisdom.

“The mottos of the sponge city are: Retain, adapt, slow down and reuse.

“Based on thousands of years of Chinese wisdom, the first strategy is to contain water at the origin, when the rain falls from the sky on the ground. We have to keep the water. The water captured by the sponge can be used for irrigation, for recharging the aquifer, for cleansing the soil and for productive use.

“It’s important to make friends with water. We can make a water protection system a living system,” concludes Kongjian Yu.

Kongjian Yu’s first project, Zhongshan Shipyard Park, blends “rustic landscapes and urban industry”

Whole-System, Water Balance Approach in British Columbia

The need to protect headwater streams and groundwater resources in British Columbia requires that communities expand their view – from one that looks at a site in isolation – to one that considers HOW all sites, the watershed landscape, streams and foreshores, groundwater aquifers, and PEOPLE function as a whole system.

The ‘sponge city’ metaphor is powerful and inspirational. As such, China, Berlin and Philadelphia are demonstrating that when there is a will, there is a way. Still, we urge the reader to take a moment to reflect upon their drivers for action – floods and droughts! They have learned the hard way that what happens on the land matters. And now, the ‘new normal’ of frequently recurring extremes has forced them to tackle the consequences of not respecting the water cycle.

The Challenge:

Opportunities for land use and infrastructure servicing practitioners to make a difference are at the time of (re)development. To those folks we say: share and learn from those who are leading change; design with nature; ‘get it right’ at the front-end of the project; build-in ‘water resilience’; create a lasting legacy.

Many land and infrastructure professionals in this province do know in principle what they ought to do. However, there is still a gap between UNDERSTANDING and IMPLEMENTATION. Communities could do so much more if they would capitalize on rather than miss opportunities. Apply the tools. Do what is right. Learn from experience. Adapt. Pass the baton.

The physics are straightforward: 7% additional water volume for each degree of temperature rise. This is the global part. If communities are serious about ensuring RESILIENCY, then the critical strategies and actions are those that relate to water.