World Water Day in the Okanagan

How Water Works in a Valley

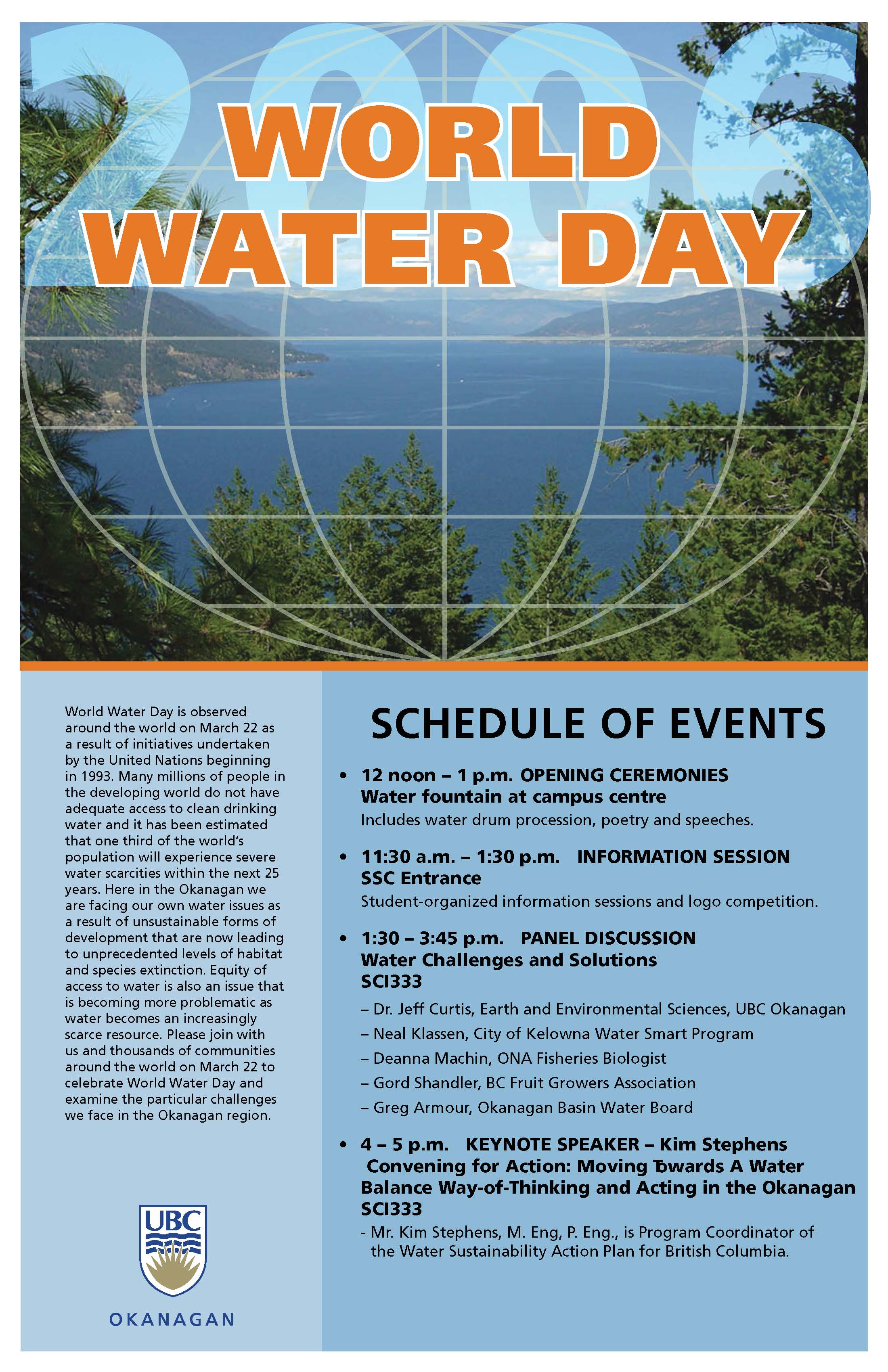

World Water Day is observed around the world on March 22 as a result of initiatives undertaken by the United Nations beginningin 1993. Many millions of people in the developing world do not have adequate access to clean drinking water and it has been estimated that one third of the world’s population will experience severe water scarcities within the next 25 years.

According to John Wagner (Assistant Professor in Community, Culture and Global Studies) who was responsible for organizing the UBC-Okanagan event, ”Here in the Okanagan we are facing our own water issues as a result of unsustainable forms of development that are now leading to unprecedented levels of habitat and species extinction. Equity of access to water is also an issue that is becoming more problematic as water becomes an increasingly scarce resource.”

According to John Wagner (Assistant Professor in Community, Culture and Global Studies) who was responsible for organizing the UBC-Okanagan event, ”Here in the Okanagan we are facing our own water issues as a result of unsustainable forms of development that are now leading to unprecedented levels of habitat and species extinction. Equity of access to water is also an issue that is becoming more problematic as water becomes an increasingly scarce resource.”

Anthropologist examines the political ecology of water in the Okanagan

When there’s only so much water to go around, who gets it and why?

It’s the kind of question UBC Okanagan anthropology professor John Wagner hopes to answer as he embarks on an exploration of how water has been used by Aboriginal peoples, European settlers, agricultural irrigation districts and communities in B.C.’s Okanagan Valley.

“I’ll be looking at the history of irrigation systems, water rights, and the policies that have been developed to manage water in the valley,” says Wagner, who lived in the Okanagan in the 1970s and returned three years ago after doing doctoral research in a coastal community in Papua New Guinea and working for two years on a sustainable fisheries research project in Nova Scotia.

“I’ll be looking at the history of irrigation systems, water rights, and the policies that have been developed to manage water in the valley,” says Wagner, who lived in the Okanagan in the 1970s and returned three years ago after doing doctoral research in a coastal community in Papua New Guinea and working for two years on a sustainable fisheries research project in Nova Scotia.

Wagner’s project, entitled From Abundance to Scarcity: the Political Ecology of Water Use in the Okanagan Valley, has received $85,864 in funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. The project is slated to run three years — but he has a longer view. “I’m going to spend the rest of my professional life working on these issues in the Okanagan,” he says.

Drenched in 2,000 hours of sunshine a year, the Okanagan is a land of contrasts: the width of a wire fence can separate irrigated leafy orchards and vineyards from native grasslands spiked with cactus and sumac. Lakes reach from north to south, and lush green corridors along creeks and streams — known as riparian areas — punctuate the landscape. Yet for all its prominence water is by no means abundant here. This fragile environment is home to one of Canada’s most arid climates.

“Over recent decades, rapid development and urbanization have resulted in habitat fragmentation and loss of biodiversity with the Okanagan now being classified as one of the most endangered habitats in the country,” says Wagner. “Riparian environments and wetlands are among the types of habitat most under siege as a result of past and current water and land management strategies. You couldn’t have all the agriculture in this valley without water, and we’ve been pretty good at redistributing water.”

But that redistribution of water raises complex issues that go back to early European settlement of the region, when government began allocating water rights.

“Water allocation practices have important social outcomes as well as ecological and economic outcomes,” he says. “Water equity is an issue to look at. The people who were getting the water rights at that time were the people who were going to develop the region. It was not the Aboriginal people.” In the Penticton area, for example, indigenous agricultural activity was well established and thriving by the end of the 1800s. Then, as water rights were granted to newly arriving farming interests in the early part of the 1900s, less and less was available for Aboriginal pastures and other agriculture.

“So they had to abandon that activity,” says Wagner.

In collaboration with the En’owkin Centre, an Indigenous cultural, educational and creative arts institution in Penticton, and the Penticton Indian Band, he has previously interviewed elders from that community and will soon be interviewing orchardists and ranchers from other communities in the Penticton area. “We want people to describe the changes they’ve seen in water use during their lifetimes,” he says.

It is a big project, but ultimately Wagner hopes to be able to share his findings with water managers, guiding tomorrow’s stewardship of a precious and limited natural resource. To that end he will also be studying the operation of water management organizations in the valley.

“There are a lot of institutions in the Okanagan with authority over water and water quality, but they’re not co-ordinated,” says Wagner.

“The hope is that by studying the institutional structure of water management organizations here we will be able to find ways to manage water in a more sustainable and equitable manner.”

Acknowledgment:

Article by Bud Mortenson reproduced with thanks from UBC Reports / Vol 52 / No. 4 / April 6, 2006